Ponzi Schemes and Theft Losses – What to do if there is NO Safe Harbor?

In March of 2009, the IRS issued two documents to explain the “theft loss” deduction for tax purposes and to ease the administrative burdens for those claiming tax deductions and refunds for theft losses from Ponzi Schemes.

One document known as Revenue Ruling 2009-9, (the “Revenue Rule”) spelled out in detail, the general law of theft loss deductions and Ponzi Schemes in particular.

The second I.R.S. document spelled out certain conditions under which I.R.S. would allow theft loss deductions for Ponzi Schemes without audits and administrative slow down. This document was known as Revenue Procedure 2009-20 and it spells out a tax concept known as a “Safe Harbor”. If the Taxpayer stays within the conditions of the Safe Harbor, their tax deduction was safe.

A Safe Harbor is a tax position spelled out by the I.R.S. defining guidelines within which the I.R.S. will not challenge a Taxpayer’s tax position, so long as the tax position fits within certain parameters demanded by the I.R.S. The I.R.S. knows that the Taxpayer would win in court within the parameters set in the Safe Harbor. Therefore, the I.R.S. says, let’s not fight it but rather formalize it.

However, there are many reasons a Taxpayer victim of a Ponzi Scheme will either not fit in the Safe Harbor or will be forced to waive valuable tax rights in the event they choose the Safe Harbor. Therefore it makes sense to study how to deal with the I.R.S. if you have a theft loss and you will not or cannot use the Safe Harbor.

I. No Access to Safe Harbor?

The best example of when a Taxpayer-victim will not be entitled to the Safe Harbor for not meeting a “Safe Harbor” rule is found at Section 4.02 of the Safe Harbor which holds that there is no “theft” for purposes of the (Safe Harbor) unless:

(1) The lead figure (or one of the lead figures, if more than one) was charged by indictment or information (not withdrawn or dismissed) under state or federal law with the commission of fraud, embezzlement or a similar crime, that, if proven, would meet the definition of theft for purposes of § 165 of the Internal Revenue code and §1.165-8(d) of the Income Tax Regulations, under the law of the jurisdiction of which the theft occurred; or

(2) The lead figure was the subject of a state or federal criminal complaint (not withdrawn or dismissed) alleging the commission of a crime described in Section 4.02(1) of the Revenue Procedure, and either –

(a)The complaint alleged an admission by the lead figure, or the execution of an affidavit by that person admitting the crime; or

(b) A receiver or trustee was appointed with respect to the arrangement or assets of the arrangement were frozen.

This part of the Safe Harbor in essence defines the status of the level of proof that the I.R.S. must see to be sure a “theft” has been committed before allowing the tax deduction. However, there are many Ponzi thefts that are entitled to a “theft loss deduction” that never reach this level of prosecutorial attention.

The definition of a “theft” for tax deduction purposes is spelled out in the Revenue Rule as follows. As one can see the definition of “theft” under the law is much broader than the I.R.S. definition of theft for the Safe Harbor. The I.R.S. defines a deductible theft as:

For federal income tax purposes, “theft” is a word of general and broad connotation, covering any criminal appropriation of another’s property to the use of the taker, including theft by swindling, false pretenses and any other form of guile . . . “theft” includes larceny and embezzlement. A Taxpayer claiming a theft loss must prove that the loss resulted from a taking of a property that was illegal and had criminal intent under the law of the jurisdiction in which it occurred. A taxpayer need not show a conviction for theft.

Many taxpayers fit this legal definition of “theft loss” for tax deduction purposes but do not fit into the Safe Harbor.

Refusing the Safe Harbor – Waiver of Amended Returns

There are also reasons why a Taxpayer may not want to use the Safe Harbor even if the Taxpayer qualifies. A major drawback of the Safe Harbor is that the Safe Harbor requires a Taxpayer to waive the right to file amended returns for prior years and eliminate only the Ponzi income in each of those years. Instead, the Taxpayer must claim the theft loss as a deduction only in the year of discovery and then carryback or carryover any excessive theft loss not applied in the year of discovery to other full taxable years.

There is a big difference between eliminating Ponzi income only, from a prior tax return and taking a theft loss for the Ponzi income in the year of discovery. It could be financially significant. After claiming a full deduction for a theft loss in the year it is discovered, losses in excess of those deducted against the income earned in the year of discovery can be carried back and carried forward. When a loss carryback or carryover is used to claim a refund it must be applied against the entire amount of income earned in the year of carryback.

The theft loss is applied against a full year’s taxable income in the carryback year or carryover year. This may average out to be a 20% tax rate for refund purposes in the year of the carryback and the actual Ponzi income (“Phantom Income”) may have been taxed at the thirty-five percent (35%) tax rate in the year it was taxed. A Taxpayer with a $1,000,000 Ponzi Scheme loss filing an amended return eliminating Phantom Income only; versus a return that claims a theft loss on that Phantom Income of One Million Dollars can mean an increase to the Taxpayer’s tax refund from $200,000 (20%) to $350,000 (35%).

Legal Support for Amended Returns

The Internal Revenue itself has recognized under certain circumstances that it is correct to amend one’s tax returns and eliminate the “Phantom Income” only from the taxable year being amended, thus making use of a tax deduction in the highest bracket.

Therefore the Taxpayer must think the calculations through before waiving the right to file an amended return that will eliminate only the Ponzi Scheme income.

Claw Backs

Another reason not to accept the Safe Harbor is if the Taxpayer is concerned that the Taxpayer may be subject to a “Clawback” as part of a Ponzi Scheme mess. If so, the Taxpayer must waive another valuable tax right in order to take advantage of the Safe Harbor. The Taxpayer is required to give up his or her rights to use Code Section 1341.1/

The Safe Harbor insists that the Taxpayer waive their right to make use of the Internal Revenue Code Section 1341 in the event they must repay money in a Clawback. Code Section 1341 gives the Taxpayer that paid tax on income from a Ponzi Scheme in a prior year who is required to pay that income back in a different year as a Clawback, a choice. The Taxpayer may take the theft loss deduction in the year that the deduction is most tax beneficial to the Taxpayer. That could be either in the year in which the payback or claw back was paid or in the year that the income that was clawed back was taxed. This is the case even if the statute of limitations is closed in the year that the original tax was paid.

This is a valuable right that the Taxpayer must waive for the benefit of the Safe Harbor.

1/ A Clawback is when the Trustee in a Ponzi Scheme after the collapse, seeks recovery against fellow Ponzi Scheme participants that may have “profited” (in a cash sense) from their participation as investors in the Scheme. For example, Mr. X invested $1,000,000 in Madoff and reported and paid tax on another $1,000,000 in Phantom Income. He also took cash distributions over the years of $1,200,000. The Trustee may wait to “claw back” the $200,000 to pay investors in the scheme that actually lost on a cash invested basis.

I. The Alternatives to the Safe Harbor

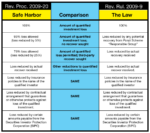

This is just a few examples of when the Safe Harbor does not fit. If it does not fit for the Taxpayer, what is the next step if one believes they have a theft loss? The best way to analyze the Taxpayer’s position is to actually compare the Revenue Ruling and the Safe Harbor rules. By studying the Safe Harbor and the law together one can see how to claim the benefits of the Safe Harbor without the Safe Harbor.

Actually, the reader will see that the two documents are really not that far apart and there is in fact complete agreement upon several points between the two documents. First we will examine where the documents differ and how to deal with the differences so that a theft loss deduction can be claimed outside of the Safe Harbor. Then we will see where they agree.

Defining Theft Loss

The two documents differ regarding the definition of the “theft” that will support a deduction. This we have already discussed. In order to use the Safe Harbor, the “theft” must be shown by a state or Federal indictment, etc. The Revenue Ruling recognizes clearly that for income tax purposes the word “theft” has a broader definition. The Safe Harbor, however, requires not only that for there to be a theft, it must result from conduct by individuals charged by an indictment, information or complaint that has been filed against the perpetrator of the theft.

This author has found that when the theft does not reach the level established in the Safe Harbor but is a theft for state criminal purposes, it is time to turn to a criminal lawyer in the state in which the theft occurred. If the incident is a theft under state law the Taxpayer should obtain a legal opinion from a criminal lawyer under the laws of that particular state that the taking of property amounted to a criminal theft under that state’s law. This is strong proof of the theft for tax purposes.

The law is clear that a taxpayer need not show a conviction for theft in order to obtain a theft loss deduction.

Year of Discovery

There are two other places where the Safe Harbor sets standards different from the law as described in the Rev. Ruling. These are the definitions for the Year of Discovery and the Amount of Deductibility of the Theft Loss in the Year of Discovery.

Both the Revenue Ruling and the Revenue Procedure are in agreement that the law requires that the theft loss deduction must be taken in the year of discovery. However, the two documents differ on defining the “year of discovery”

To enjoy the benefits of the Safe Harbor, the Taxpayer must accept that the year of discovery is directly related to the year in which the indictment, information or complaint against the perpetrator which led to the theft has been filed. Therefore, under the Safe Harbor, a fixed “year of discovery” is tied directly to the Federal or state actions against the perpetrator.

This can be a very important difference. Keep in mind that in many business and theft loss cases there will be no indictment, etc. as required by the Safe Harbor to prove theft. The Taxpayer, not in the Safe Harbor, must not only be able to prove a theft loss, he or she needs to show the year in which the theft was discovered. The “year of discovery” is proven by gathering the pertinent evidence to the year of discovery. Evidence must be preserved that shows when the fraud was first discovered. This can be such things as notices of the collapse of the investment, meetings with lawyers or other professionals regarding the collapse, letters to perpetrators, income tax returns that prove the Taxpayer either still believed in the Ponzi Scheme at a particular point in time and any other facts.

The courts in deciding the year of discovery of a theft have agreed on several principles that provide further guidance. In determining the reasonableness of a taxpayer’s belief of loss at a particular time, the courts recognize they must be practical and take the individual facts of each case on its merits.

The relevant facts and circumstances are those that are known or reasonably could be known as of the end of the tax year for which the loss deduction is claimed. The only test is foresight, not hindsight. Both objective and subjective factors must be examined.

The law provides good guidance on the year of discovery and it is very much the year in which the ordinary reasonable person knew they had a loss from the collapse of investment.

In this regard it would seem that the Safe Harbor leaves no room for flexibility whereas the case law of the Rev. Rul. are not as exacting on the determination of the year of deductibility. Proof will be the key.

Amount of Deductibility in the Year of Discovery

The only other major concept where the Safe Harbor differs from the law is in dealing with exactly how much of a theft loss can be recognized and deducted and taken advantage of in the year that it is discovered.

TO BEGIN WITH, BOTH DOCUMENTS AGREE THAT THE TOTAL AMOUNT OF A THEFT LOSS IS EQUAL TO THE TAX BASIS OF THE LOSS.

This discussion deals with how much of that loss can be taken as a deduction in the year of discovery only. There are other standards that determine the timing on the deduction for those losses not claimed in the year of discovery.

The standard that defines exactly how much of that total amount is deducted in the year that the theft is discovered is defined as the total amount of the loss reduced by any amount that represents a “reasonable prospect for a recovery”. To the extent there is a reasonable prospect of recovery, there will be no deduction in the year of discovery.

The Taxpayer’s legal rights as of the end of the year of discovery are all important and need to be studied to make a proper decision. One of the facts and circumstances deserving of consideration is the probability of success on the merits of any claim brought by the Taxpayer. This is because the filing of a lawsuit may give rise to an inference of a reasonable prospect of recovery. However, the inference is not conclusive or mandatory. The inquiry should be directed to the probability of recovery as opposed to the mere possibility. A remote possibility of recovery is not enough; they must be a reasonable prospect of recovery at the time the deduction was claimed, not later.

In the event the deduction is not taken in the year of discovery, it will eventually be taken as a deduction in later years. However, if the theft loss is not taken in the year of discovery it must meet a higher standard of proof to be deductible in any other year. Eventually at that point in time when the Taxpayer can “ascertain with a reasonable certainty” that there is no prospect of recovery, any unclaimed theft losses may be taken. This could be a significant long period of time to delay deduction for theft losses.

Safe Harbor – Fixed Percentages

The Safe Harbor has definitely delivered the Taxpayer a favor in clarifying the amount of the theft loss deductible in the year of discovery by clearly defining certain percentage amounts that can be deducted under varying circumstances in the year of discovery to account for “contingent recoveries”.

Prior to the establishment of these fixed percentages by the I.R.S., the Taxpayer has always been dependent upon case law and accounting presentations to prove the amount of the deduction available in the year of discovery.

There are three groups of potential recoveries that both documents agree will reduce a theft loss in the year of discovery. That is three groups that represent a “prospect of recovery” in the year of discovery.

1. Recoveries from Insurance, Guarantees and Agreement to Limit Losses.

Essentially the Safe Harbor and the Rev. Rul. both agree that any amount of the loss claimed in the year of discovery as a deduction must be reduced by amounts actually recovered in the year of discovery or amounts that will be recovered as a result of insurance policies of any other contractual arrangements or guarantees that would repay the taxpayer for any of the theft loss claimed. This also includes government insurance companies such as the Securities Investors Protection Corp.

However, “all reasonable prospects of recovery” cannot be so easily quantified. THIS IS WHERE THE SAFE HARBOR IS MOST HELPFUL. THE SAFE HARBOR PROVIDES TWO (2) FIXED PERCENTAGES FOR THE TWO GROUPS THAT QUANTIFY THE BALANCE OF POTENTIAL UNKNOWN AND CONTINGENT RECOVERIES THAT COULD OTHERWISE REDUCE THE AMOUNT OF THEFT LOSS IN THE YEAR OF DISCOVERY.

Those two potential contingent amounts of recovery are as follows:

2. Recovery from those Responsible for the Ponzi Scheme. “The Responsible Group”. The Safe Harbor states that if the only people from whom the Taxpayer expects recovery of the Taxpayer’s total theft loss are the people who perpetrated the crime, then in the year of discovery the Taxpayer may deduct 95% of the total theft loss.

It is presumed by the I.R.S. that the Taxpayers will not recover more than 5% of the Taxpayers’ loss from the actual perpetrators.3/

If the Taxpayer is not in the Safe Harbor the Taxpayer will still be able to deduct 95% or more of the total loss. However, without the Safe Harbor the Taxpayer is going to have to prove his or her case. There is at least one case that supports that the 5% reduction in the loss, in the event the perpetrator is the only source of recovery, is acceptable to the courts.

3/ This “concession” of 5% that is reflected in the Safe Harbor Standard obviously reflects the long history of case law and experience that shows that recovery from the perpetrators of the Ponzi Scheme’s themselves will rarely be more than 5% as recovery towards the overall loss. As major fees and litigation are involved in obtaining this recovery. These fees reduce the recovery.

The Taxpayer will need to establish that he or she is not seeking any other source of recovery than from the Perpetrators and that the chances of receiving a refund from the perpetrators is no more than 5%. The Taxpayer will need to provide the proof necessary to establish that the amount (most likely from the Trustees own records), that they will recover from the Perpetrators will be no more than 5% of their loss.

The big difference here to be overcome by the Taxpayer who cannot use the Safe Harbor is that the Taxpayer must be responsible to provide proof that the Trustees’ recovery will not be significant. This can be done with good accounting.

3. Recovery from Third Parties. The Safe Harbor also provides the Taxpayer with a percentage amount to quantify another unknown potential recovery that could reduce what a Taxpayer may claim as a deduction in the year of discovery. The Safe Harbor provides that if a Taxpayer is also seeking recovery from third parties by litigation such as the major brokerage firms or accounting firms, etc. that may be responsible for the fraud; in this situation, the Safe Harbor will reduce the amount of theft loss deduction in the year of discovery by an additional 20% of the total amount of the theft loss to account for the potential recovery loss.

In other words, if a Taxpayer is suing third parties and depending upon distributions from a Trustee representing the perpetrators, the Taxpayer must reduce their total theft loss by 25% in the year of discovery until these issues are resolved.

Again, the Taxpayer who cannot rely on the Safe Harbor is going to have to prove their case. It is here where good forensic accounting may make a major difference and where a taxpayer may be able to prove that their “third party recovery” will amount to certainly no more than and possibly even less than the 20% amount allowed under the Safe Harbor rules.

DOCUMENTS IN AGREEMENT

As we stated, there are also many places where the Safe Harbor and the law agree.

Phantom Income as a Basis for Theft Loss.

The Rev. Rul. And the Safe Harbor do not disagree on the legal point that Phantom Income, which has been taken in as income and upon which tax has been paid by a Ponzi victim, may be the subject of a theft loss and becomes part of the tax basis that is deductible as a theft loss.

In order to be prepared to establish that tax has been paid on Phantom Income, all Taxpayers should include in their claim for refund, every tax return upon which Phantom Income appears as part of any submission to the I.R.S. There is no reason not to include each and every one of the Taxpayer’s income tax returns and any other vital information relevant from previous years to prove Phantom Income. There will be many other records that will support the payment of taxes on Phantom Income. All of this needs to be preserved.

Finally, both documents are in agreement on certain legal points that make life easier for the Taxpayer. These are:

Ordinary Income Deduction

Both documents agree that the theft loss deduction is a deduction of ordinary income and is entitled to be used as a net operating loss carry back or carry forward.

A Business Deduction

Both documents agree the theft loss deduction in a Ponzi Scheme is a business deduction that is not reduced by any of the percentage dollar limitations applicable to other types of casualty and theft losses.

Pass Through Entities

Both the Rev. Rul. and the Safe Harbor Agree those Taxpayers in “pass through entities” such as limited liability companies and partnership will be entitled to take their portion of any of the theft loss directly in spite of the fact the loss is in the name of the entity.

Summary

In summary, the Safe Harbor is just the starting point for those who are victims of Ponzi Schemes and other business and investment related theft loss that do not meet its conditions. Tax refunds can be obtained without the Safe Harbor; sometimes it is even more valuable without it.

The road towards a tax refund will be slower and the Taxpayer is advised to gather the most evidence one can get their hands on to prove the “year of discovery”, the amount of the “Phantom Income” and the actual “reasonable prospects of recovery” in the year of discovery.

With the right evidence and the law on your side, theft losses from Ponzi schemes can lead to the same refunds as the Safe Harbor and even more, since interest will be paid on the refund from the time the taxes were paid in certain situations. This might not occur under the Safe Harbor, the Taxpayer may be better off without the Safe Harbor in many situations.

Personal Comments

I have always said the Ponzi Scheme is one of the best things that has happened to the I.R.S. in a long time. The reader will have heard the names Madoff, Sanford, Nadell, etc. Let’s assume that all together they created $200 Billion Dollars of Phantom Income, almost all of which was taxed by the I.R.S. in the 35% tax bracket. In other words I.R.S. made $70 Billion from the Ponzi Schemes. (35% x $200 Billion)

I have seen in my practice that a tremendous amount of this valuable theft loss tax deduction is not being used properly or at all by individual Taxpayers. It is going completely to waste because it

(i) it is not properly being used before the death of the Taxpayer, or

(ii) it can be used only against income that is taxable in the 15% tax rate because the Taxpayer’s income is now so low due to their Ponzi Scheme loss; or

(iii) deductions are being wasted by poor professional advice or lack of knowledge.

I believe the average total amount of Ponzi Scheme refunds that will be made by the I.R.S. will be at a tax rate that averages less than 15%. The I.R.S. will receive $70 BILLION in taxes from “Phantom Income” and after holding the Taxpayers’ money for ten years will return about $25 BILLION in refunds.