Favorable Tax Consequences – Ponzi Schemes And The Clawback

July 2013 Update

The taxation of the Clawback in Ponzi Schemes and certain other financial theft losses.

Now that the Ponzi Schemes, after Madoff have started to mature, they have become more numerous and trustees are clawing back billions from innocent investors who may have profited from their investment in the fraud. The largest recovery for people who must pay Clawbacks, will be from tax refunds. A taxpayer in California or New York City might receive more than 50% of their money back just in tax losses.

We are working on a new seminar “Realizing the maximum value in losses suffered from Ponzi Scheme Claw Back payments”

This online seminar will include a presentation from a seasoned litigation attorney with extremely good credentials who will explain the nature of the Clawback in Ponzi Scheme frauds from a litigator’s standpoint.

This will be of great help to this new class of victims who are targets of a Clawback and do not know where to turn for help.

If you would like to be alerted when this seminar becomes available – please “like” us on Facebook. Or fill out the form on the bottom of the page.

REPORT TO CONGRESS:

- The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on the Customer Outcomes in the Madoff Liquidation Proceeding. Download full 80-page report .

New IRS RULING:

http://www.irs.treas.gov/uac/FAQs-Related-to-Ponzi-Scenarios-for-Clawback-Treatment

- The most recent Internal Revenue Service ruling allows clawback victims of Ponzi schemes to maximize their tax refunds and deduct their losses in years that would otherwise be closed by the Statute of Limitations. This is in the event the deductions are more valuable in the earlier years for purposes of tax refunds. The article below describes completely the advantages of how to make use of Code Section 1341.

By Richard S. Lehman, Esq.

(download this article as a .pdf)

Most of us are familiar with the concept of the Ponzi Scheme. An investment built on phony profits that crashes and burns, financially devastating many.

What is less familiar is the fact that an investor in a Ponzi Scheme cannot only lose all of their investment. Investors in Ponzi Schemes can also be forced to pay back additional moneys earned from the Ponzi Scheme years before it exploded. This is what is known as a clawback.

As the baby boomers age, the fear grows that they will outlive their remaining financial resources. After an internet bust, a real estate bust, a Wall Street giveaway, a worldwide recession and banks now borrowing money at less than one percent while the boomers are paying 25% on their credit cards, the boomers are now prime targets for Ponzi Schemes. Multibillion dollar Ponzi Scheme failures are announced with regularity and the list will grow.

With the entire group of baby boomers seeking alternative investments to make sure they are secure, financial frauds, especially Ponzi Schemes will surely grow as the baby boomers reach their peak. Over 70 million people will be looking for the same high rates that will not exist. The term “clawback” will become more familiar as those Ponzi Schemes self destruct.

The definition of a Ponzi Scheme is provided by the I.R.S. and the legal principles governing such a scheme are found at Rev. Proc. 2009-20 at Section 4.01 and Rev. Rul. 2009-9. The I.R.S. calls a Ponzi Scheme a Specified Fraudulent Arrangement.

Specified fraudulent arrangement. A specified fraudulent arrangement is an arrangement in which a party (the lead figure) receives cash or property from investors; (ii) purports to earn income for the investors; (iii) reports income amounts to the investors that are partially or wholly fictitious; (iv) makes payments, if any, of purported income or principal to some investors from amounts that other investors invested in the fraudulent arrangement; and (v) appropriates some or all of the investors’ cash or property.

A Ponzi Scheme will by its very nature reward certain innocent investors to prove the scheme works; and ultimately crash on those investors that left their funds in the scheme to keep earning the large returns or new investors who came in just before the crash. Certain investors will receive their principal and outsized profits while some lose it all.

Once the Ponzi Scheme crashes, there are insufficient funds to meet the obligations and a Trustee is appointed for the Estate of the perpetrators of the Ponzi Scheme. The Trustee is in fact the continuing entity of the perpetrators. However, this Trustee has very broad powers to recoup funds for the general estate so that the Trustee can provide equity among the investors who all have been in the same investment but some have lost while others have won. This is the clawback.

Clawback is a term used to describe the power that a trustee has to regain assets of a debtor that should have been available as part of the bankruptcy estate, but were removed or hidden from the Trustee by the debtor by means of preferential or fraudulent transfers.

The Bankruptcy Code authorizes the trustee to reach back 2 years to recover fraudulent conveyances. There are two general types of fraudulent conveyances (a) a transfer made with actual intent to hinder, delay or defraud creditors (i.e. an actual fraudulent transfer) and (b) a transfer made for less than reasonably equivalent value or fair consideration by an entity that is insolvent or undercapitalized (i.e. a constructive fraudulent transfer).

The Trustee has varying powers in this situation to recoup funds. Without explaining these laws in detail, suffice it to say, the Trustee may recoup profits earned by an innocent investor in a Ponzi Scheme. The Statutes governing this case are very much like strict liability where the innocent investor, (the “Taxpayer”), does not need any wrong intention to be liable. There is liability imposed on the innocent Taxpayer because the Ponzi Scheme perpetrator and not the defrauded Taxpayer ran a Ponzi Scheme. Nevertheless, the Taxpayer was paid from the scheme and can be liable for the return of profits and principal.

As an example, assume Mr. Jones invested $1.0 Million in a Ponzi Scheme and earned $1,500,000 in securities income. The income was distributed to Mr. Jones and Mr. Jones paid tax on the income. The balance of the income was spent by Mr. Jones. Assume the Ponzi Scheme collapses with Mr. Jones holding a balance in his account of $1.0 Million that is lost. Since Mr. Jones’ cash out exceeded his cash in, he may be forced to repay certain income to the Trustee, in spite of his $1.0 Million loss of principal.

The Tax Law

When this “clawback” occurs, generally the income clawed back from the Taxpayer will be deductible by the Taxpayer in the year it is paid. However, often the deduction in the year the clawback is paid may occur at a much lower tax bracket than the tax bracket that was applicable to the income when it was included in income.

To provide for tax equity under specific circumstances, the Internal Revenue Code permits a taxpayer who includes an item in gross income in one tax year and pays tax on that item and who is compelled to return the item in a subsequent year, to calculate the deduction on the amount that is returned in a unique way. This is known as the “Mitigation” section and is found in Section 1341 of the Internal Revenue Code. (the “Code”). The Mitigation provision permits a Taxpayer to calculate the refunded money either as a deduction in the year the refund is paid or a higher tax rate in the year that the refunded sum may have been included in income.

The answer to whether a Taxpayer may recover under the Mitigation Section starts with the legal principle known as the “claim of right doctrine”. It was enunciated in 1932 by the Supreme Court and stands for the proposition that income received in a particular year is subject to tax when received even though it may be returned in a later year.

If a taxpayer receives earnings under a claim of right and without restriction as to its disposition, he has received income [on] which he is required to [pay tax], even though it may still be claimed that he is not entitled to retain the money, and even though he may still be adjudged liable to restore its equivalent.

The Mitigation provision was needed to cure the inequities caused by this rule. Since the passage of the Mitigation provision, several judicial doctrines have evolved and controversies still exist in interpreting the Mitigation section. Some of these have lasted for over 50 years. There are still different judicial views of certain of the requirements that needed to be met to enjoy the benefits of Code Section 1341.

The case of Pennzoil, Quaker State, that was first decided in the Taxpayer’s favor by the Federal Court of Claims in 2004 and later reversed by the Federal Court of Appeals in 2008 clarified matters in this area of the law a great deal but also, to some extent continued the controversy. Together, the two courts defined the five separate requirements that must be met to enjoy the benefits of the Mitigation section and the judicial doctrines that have developed to clarify the law. The two analyses by these courts are helpful in better understanding this Mitigation section. The two courts together explored each requirement of the section thoroughly.

The Requirements of § 1341(a)

A clawback may require both a repayment of the Taxpayer’s previously taxed income earned from the Ponzi Scheme and can also require a repayment of a Taxpayer’s principal investment.1/

The courts in the Pennzoil case considered the availability of Code Section 1341 to a situation where the Pennzoil Company refunded certain amounts of money to independent crude oil producers for alleged price fixing.

Pennzoil ultimately settled the lawsuit for $4.4 Million which it tried to deduct in the prior years when the crude oil was sold instead of the year of payment. Because of the particular facts of Pennzoil, the court in Pennzoil had to deeply analyze each one of the first four requirements of Code Section 1341 to determine its applicability in the Pennzoil situation.

The first court ruled in favor of Pennzoil, the Taxpayer, and permitted the deduction and the Mitigation treatment of Code Section 1341. However, the Appellate Court eventually found in favor of the I.R.S. and that Pennzoil could not use Code Section 1341.

Ultimately the higher court in Pennzoil decided that though Pennzoil may have met many of the requirements of Code Section 1341, it was not entitled to 1341 treatment. The discussion of the requirements by the two courts is invaluable.2/

The Pennzoil Courts both stated that the language of §1341 requires the Plaintiff to prove that five factors have been met: The emphasis supplied below was the Courts.

(1) an “item” must have been “included in gross income for a prior taxable year (or years)”;

(2) “because it appeared that the taxpayer had an unrestricted right to such item”;

(3) a “deduction” must be “allowable for the taxable year” in which the item is repaid;

As will be discussed, a divided Appellate Court’s with one dissent believed the main reason for denying Pennzoil the benefits of the Mitigation section was under a different exception to the Mitigation provision.

(4) “because it was established after the close of such prior taxable year (or years) that the taxpayer did not have an unrestricted right to such item or to a portion of such item”; and

(5) “the amount of such deduction” must exceed $3,000.

These requirements seem to be relatively straight forward and certainly there can be no question about the interpretation of the fifth requirement. However, several of these requirements are not as straight forward as they look. Each has to be understood within the tax world, where often there are exceptions to make sure special provisions, like the Mitigation provision, applies only to those that are legally deserving of them.

The fact that two very learned courts, the Court of Claims (the “Lower Court”) and the Court of Appeals (the “Appellate Court”) differed on whether the requirement of an “item” of income has been met, shows how technical this section is. This is in order to insure that only a certain category of Taxpayer receives this Mitigation.

1. THE FIRST REQUIREMENT FOR MITIGATION IS THAT AN “ITEM” MUST HAVE BEEN INCLUDED IN GROSS INCOME FOR A PRIOR TAXABLE YEAR (OR YEARS)

Both Courts in Pennzoil addressed this two part question, first by determining whether the Taxpayer possessed an “item”, and next whether that item was “included in gross income.” I.R.C. § 1341.

Guidance as to what is an “item” of gross income is found in the I.R.S. Code Section 61. That Code Section provides a specific definition for gross income and a general one. Another Code Section, Section 161, provides an allowance for deductions that are also specifically listed in the Code. The income “items” that might be included in income in a Ponzi Scheme might include any of the following found in Code Section 61.

Except as otherwise provided . . . . gross income means all income from whatever source derived, including (but not limited to) the following items:

- Gross income derived from business;

- gains derived from dealings in property;

- interest;

- rents;

- royalties;

- dividends;

- annuities;

- income from life insurance and endowment contracts;

- pensions;

- income from discharge of indebtedness;

- distributive share of partnership gross income;

- income in respect of a decedent; and

- income from an interest in an estate or trust.

It seems that there may actually be different tax treatments insofar as the Mitigation provision is concerned. The “profits” that create the false Income in some Ponzi Schemes could very well be excluded from the Mitigation problem because they are a result of phony “inventory sales”. However, it is generally going to be more likely that “phantom income” (income that never really existed) will consist of interest, dividends or many of the other items listed as income in the Code Section.

The issue of whether a clawback payment represents an “item” of gross income for purposes of Mitigation goes a step further than simply qualifying under Code Section 61. In addition, the courts will review the “item” to determine whether the item resulted from the same circumstances as those of the original inclusion. This is known as the “same circumstances” test.

The Lower Court in the Pennzoil case found that the requirement that the Taxpayer’s $4.4 Million obligation to repay suppliers as a result of Pennzoil’s alleged price fixing was from the same circumstances as the original inclusion of funds.

However, the Appellate Court reversed the Lower Court and differed as to whether Pennzoil’s refund met the same circumstances test. The Court defined the test as follows:

“The claim of right” interpretation of the tax laws has long been used to give finality to [the annual accounting] period, and is . . . deeply rooted in the federal tax system” Section 1341 is an exception to the claim of right doctrine. The “same circumstances” test, formulated by the Tax Court, “provides appropriate, workable limits” to that exception. The limitations are that “the requisite lack of an unrestricted right to an income item permitting deduction must arise out of the circumstances, terms and conditions of the original payment of such item to the taxpayer.”

Several examples were shown of this principle. In the Bailey case, the taxpayer received dividends, salary, and bonuses as the officer of a corporation, and later paid a civil penalty for violating an FTC order in the work he did for the company. The taxpayer claimed that his payment of the penalty restored an item of income included in his gross income in previous years. The Court then invoked the “same circumstances” test to deny 1341relief, reasoning that the FTC penalty “arose from the fact that Bailey violated the consent order, and not from the circumstances, terms and conditions of his original receipt of salary and dividend payments: and that “the amount of the penalty was not computed with reference to the amount of his salary, dividends and bonuses, and bears no relationship to those amounts.”

In other examples it was shown that the Court barred application of § 1341 where the item included in income (medical fees from Blue Cross) “did not arise out of the same circumstances, terms and conditions” as taxpayer’s restitution payment for fraud to Blue Cross. The Court denied Mitigation relief where corporation’s revenues in prior taxable years “bore no relationship to the amount of the obligation to pay for environmental clean-up” in later years and the court denied the Mitigation provisions to a taxpayer’s settlement of claims for negligence and breach of fiduciary duty arising out of her business because they had “no connection” to consulting fees she received after selling the business.

In short, where the later payment arises from a different commercial relationship or legal obligation, and thus is not a counterpart or complement of the item of income originally received, the “same circumstances” test preludes application of § 1341.

It would seem that the “same circumstances” test is generally going to be satisfied on the very face of the Ponzi clawback transaction. Had it not been for the Ponzi Scheme Investment, there would be no tax on or reporting of income transactions that would comprise a clawback.

All income in a Ponzi Scheme is reported as a direct result of the Scheme. The clawback obligation is a direct result of that scheme and the payment from the scheme.

As a practical matter, any Settlement agreement that is being reached in a Ponzi Scheme should include language to clarify the “item” being refunded. For that matter, any settlement agreement including a clawback should be reviewed by tax counsel prior to finalization.

Included in Gross Income

The second part of the first requirement for Mitigation is that the “item” must have been included in gross income for a prior taxable year. This in fact means included in gross income and subject to taxation in that prior years. This is typically not controversial in the case of a Ponzi Scheme as the income from the scheme, whether actual or phantom, will have been reflected in the tax returns.

2. it Appeared that the Taxpayer had an Unrestricted Right to Such Item.

The next item requires that the Taxpayer had an apparent right to the gross income that the taxpayer reported in the prior year. For quite a while prior to the Pennzoil case, there were differences of opinion that separated this requirement into three different areas. Did the taxpayer have an “apparent right”, did the taxpayer have an “actual right” or did the taxpayer have “no right” at all?

As to the first two of these items, some courts embraced a distinction between an actual right and an apparent right, while others found that an “apparent right” encompassed an “actual right”. The Lower Court in Pennzoil found this distinction to be meaningless. The rationale was not challenged by the Pennzoil Appellate Court.

The Pennzoil lower court found that the Mitigation statute was ambiguous in defining an “apparent right” to the included income. There was no binding case law regarding the actual and apparent dichotomy. The Court therefore turned to the legislative history of § 1341. The legislative history does provide guidance as to the meaning of the term “apparent” in § 1341. In the House and Senate Committee Reports, the legislature states that § 1341 will apply “[if] the taxpayer included an item in gross income in one taxable year, and in a subsequent taxable year he becomes entitled to a deduction because the item or a portion there is no longer subject to his unrestricted use.” Pennzoil held that due to this, an actual right must be included in the definition of an apparent right for purposes of § 1341.

Though the Pennzoil Court of Claims case was reversed, it was not reversed as to this finding and the Court’s analysis is still very helpful.

This reasoning of the Court is important here because the Court stresses that since the Mitigation Provision is remedial it should be interpreted in favor of the Taxpayer. Therefore, § 1341 should be interpreted broadly to effectuate congressional goals. Any doubts regarding the plain meaning of the statute must be resolved against the government and in favor of the taxpayer.

Section § 1341 is a relief provision . . . This would encourage taxpayers to return funds they may have received in appropriately by neutralizing all negative tax impacts of the prior taxation. It should be remembered that Section 1341 is not a tax deduction provision. It does not grant taxpayers a tax benefit for amounts that are not otherwise deductible.

Pennzoil may even stand for the proposition that when a taxpayer reports an “item” as taxable income in a tax return; a prima facie case is made that the taxpayer believed the income was the Taxpayer’s. As the court in Pennzoil put it:

Since Quaker State took into income the [item] it is clear that Quaker State believed that it had a right to that income”.

Certainly in the case of the Ponzi Scheme every objective indication is that there is an apparent right to income that is being reported by that investor. It is stated on the investor’s tax return, available for distribution to them until the crash comes and as can be seen by the many lives devastated by Madoff and others, counted on by the Ponzi investor as real.

The Claim of Wrong Exception

To be entitled to the Mitigation, a Taxpayer must not have only had an apparent right to the reported income; the Taxpayer must have not wrongfully obtained that income.

Intertwined in this issue of an “apparent right” to the income is a doctrine known as the claim of wrong exception. This means that if the Taxpayer had no right at all to the income when it was received, it could not receive Mitigation treatment if later that income was refunded. It is often raised by the I.R.S. to deny the Mitigation section.

Like the “same circumstances” doctrine, the claim of wrong doctrine originates in the case law arising out of the claim of right deduction. The I.R.S. position is that a taxpayer cannot have any right to income for purposes of Code Section 1341, even an “apparent” right to income, if the original claim of the income was “wrongfully obtained. This doctrine has been applied in cases of embezzlement, smuggling, kickbacks and ill gotten gains and rarely in a civil fraud setting.

One thing that is clear about the “claim of wrong doctrine”; is that the doctrine cannot exist in a situation where there is no intentional wrongdoing. It certainly does not exist in the typical Ponzi Scheme victim Taxpayer where lending or investing money with a highly respected and presumably trustworthy and wealthy member of the community (who turned out to be a con man) cost the Taxpayer financial loss and sometimes even their life’s fortunes.

The Court in Pennzoil explained the claim of wrong in this fashion:

. . . [I.R.S.] argues that [Taxpayer’s] alleged price-fixing means that it could not have believed [the Taxpayer] had an unrestricted right to the income it earned between 1981 and 1995. [This] position is buttressed by the Federal Circuit’s decision in Culley, in which the court held that a plaintiff could not have believed that he had an unrestricted right to income, since the income was gained through an intentional wrongdoing. [Pennzoil] has been neither indicted nor convicted, and [Pennzoil] asserts that it “believed at the time it made the payments to the independent oil producers that it paid them a fair and honorable sum.” In fact, in the antitrust settlement, [Pennzoil] did not even admit liability.

The Taxpayer who is subject to a clawback in the typical Ponzi Scheme is much more pristine than Pennzoil. The Taxpayers who invest money are paid interest or other types of income for their loans or investments, receive their funds, pay tax on them and have given it all back through no fault of their own.

3. THE THIRD REQUIREMENT FOR MITIGATION IS THAT A DEDUCTION MUST BE ALLOWABLE FOR THE TAXABLE YEAR IN WHICH THE ITEM IS REPAID

The third requirement is that in the actual year of payment that the Taxpayer pays the clawback, the payment must be a permitted deduction that is allowable for the taxable year in which the repayment is made. Simply put, it means that a clawback paid in the year 2011, for example, must be allowed as a deduction for that payment in the year 2011. If the payment presents Ponzi profits paid to a Taxpayer and reported for tax purposes in 2006 it will not be allowed to be deducted at the rates applicable for 2006 unless a deduction is permitted in 2011, the payment year.

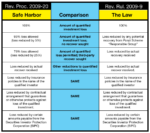

Whether a loss from a Ponzi Scheme is deductible is a question already decided in the affirmative by the Internal Revenue Service. In the year 2009, the I.R.S., in response to all of the pending claims for refund generated by the Madoff situation, produced two public documents; Rev. Procedure and Rev. Ruling. Those documents make it clear that victims of a Ponzi Scheme are entitled to a deduction for their loss relating to that Ponzi Scheme. The Ponzi Scheme which is ultimately responsible for a clawback is the same Ponzi Scheme that caused any of the other losses.

This is the law since the I.R.S. has found that a Ponzi Scheme is a transaction entered into for profit. There is no question that the Taxpayer’s investment in a Ponzi Scheme is an investment entered into for profit. Revenue Ruling 2009-9 makes it clear that Code Section 165 (c)(2) applies to Ponzi Schemes as transactions entered into for profit. A deduction for a theft loss would be available in 2011. The clawback payment should not be any different.

The Deduction – The Safe Harbor – The Waiver Of The Mitigation Provisions?

The Revenue Procedure that the I.R.S. issued in 2009 outlined an easy administrative procedure to obtain deductions resulting from a Ponzi Scheme loss. A Taxpayer may find that he or she wishes to use the Safe Harbor and may also be subject to a Clawback. A Taxpayer should not use the Revenue Procedure if they are expecting a clawback without professional advice.

The Safe Harbor requires the Taxpayer to waive the right to use Code Section 1341. The question is whether the waiver of Code Section 1341 is a waiver only of that right to use 1341 on a direct Ponzi theft loss, or is it a waiver of the right to use Code Section 1341 for Clawback payment in that year also?

It is not settled whether this waiver in the Safe Harbor applies only to Ponzi Scheme loss claims or also to clawbacks in general. The IRS Revenue Ruling 2009-9, which legally justifies a theft loss deduction for Ponzi Schemes in the year of discovery, also addresses the use of Code Section 1341 by Ponzi Scheme victims applying for a direct theft loss deduction on their Ponzi Scheme losses. The Revenue Ruling says that the Code Section 1341situation does not apply. However, that Revenue Ruling implies that a “Clawback” may very well be distinguishable from a direct theft loss and may not be prohibited by the waiver of Code Section 1341that is required by the Safe Harbor. This is because there is no “restoration of funds” in a Ponzi Scheme loss. Whereas; in a Clawback just such a restoration of funds does exist.

To satisfy the requirements of § 1341 . . . a deduction must arise because the taxpayer is under an obligation to restore the income.

When A incurs a loss from criminal fraud or embezzlement by B in a transaction entered into for profit, any theft loss deduction to which A may be entitled does not arise from an obligation on A’s part to restore income. Therefore, A is not entitled to the tax benefits of § 1341 with regard to A’s theft loss deduction.

This is an accurate statement of the law on Ponzi losses. However, Revenue Ruling 2009-9, in denying that Code Section 1341 would apply to “theft losses” from Ponzi Schemes, did not consider theft losses that result from payments from “Clawbacks”.

These are the same type of losses and they are directly related to the fact that the Ponzi Scheme investor invested in a fraudulent scheme.

In fact the Revenue Ruling seems to confirm that Code Section 1341 would apply to clawbacks since all that was missing according to the Revenue Ruling was an “obligation to restore”. This is exactly what is present in a Clawback, the restoration of funds. The Revenue Ruling only considered direct losses from Ponzi Schemes where no additional payments were required. That is not that Taxpayer’s case in a Ponzi Scheme clawback.

In a clawback situation, the losses come after the Ponzi Scheme has failed and they are a result of a forced repayment, not an original payment.

4. THE FOURTH REQUIREMENT FOR MITIGATION TREATMENT IS THAT THE FUNDS MUST BE RESTORED “BECAUSE IT WAS ESTABLISHED AFTER THE CLOSE OF SUCH PRIOR TAXABLE YEAR (OR YEARS) THAT THE TAXPAYER DID NOT HAVE AN UNRESTRICTED RIGHT TO SUCH ITEM OR TO A PORTION OF SUCH ITEM”

In the fourth requirement the Statute requires that when the Taxpayer refunded the clawback monies, it must be clear that the Taxpayer did not voluntarily return funds in order to profit from the Mitigation provisions.

There was a good deal of litigation on just what was meant by the “established” requirement. This also was clarified in the Low Court in the Pennzoil case. The bottom line is that funds cannot be “voluntarily repaid” and the best proof of this can be a good faith settlement agreement reached with the clawback trustee.

The fourth requirement of Section 1341 is that income is restored to another person because it was established after the close of such prior taxable year (or years) that the taxpayer did not have an unrestricted right to such item (or portion thereof)”.

Pennzoil states that the “established” requirement is met under the following circumstances:

. . . The general rule is that a good faith, non collusive settlement agreement entered into to terminate litigation will “establish” a liability to return income, thereby establishing a lack of an unrestricted right to income for purposes of Section 1341.

The Pennzoil case analyzed the two landmark cases deciding this issue and the standard to meet the “established” requirement. The Pennzoil case analyzed both the Barrett case and the Pike case that some courts had indicated were in contradiction. However, Pennzoil pointed out there was no contradiction. In doing so, Pennzoil clarified another “doctrine” that has developed in the Mitigation provision. The doctrine of “voluntary payment”.

The Pennzoil case clarified that doctrine in this area of law also and in so doing makes it perfectly clear that the Taxpayer’s good faith efforts in the Ponzi Scheme to resist repayments of money in this fraud should meet the “established” requirement of the law.

In Barrett, the taxpayer had included profit from the sale of stock options in one year, and then in a later year, the Securities and Exchange Commission brought administrative proceedings against him on the basis of alleged insider trading. The taxpayer settled the case without admitting liability and claimed that the settlement payment deserved § 1341 treatment. Barrett held that a settlement made at arm’s length and in good faith can satisfy the “establishment” requirement of § 1341, stating:

“The source of the obligation [to repay] need not be a court judgment; however, there must be a clear showing . . . of the taxpayer’s liability to repay.”

Barrett also noted that this result “fostered the legal policy of peaceful settlement of disputes without litigation.

In contrast to Barrett was the Pike case that involved a taxpayer who bought and sold corporate stock in one year, after which an investigator found that the profit from said stock should have gone to the corporation and not the taxpayer. The taxpayer then paid the money to the corporation, without admitting that the profits belonged to the corporation, and avoiding controversy so that he did not suffer harm to his professional career. The Pike court stated that, although “a judicial determination of liability is not required … it is necessary under section 1341 for a taxpayer to demonstrate at least the probable validity of the adverse claim to the funds repaid.”

Although the holdings in Pike and Barrett are different due to distinguishable facts, the point of law that they stand for was not. The primary distinction is that, in Pike, there was no suit against the plaintiff for repayment of money, which makes it more likely that the taxpayer acted voluntarily in paying the money and less likely that the taxpayer can “demonstrate at least the probably [sic] validity of the adverse claim.” Voluntary restitution will not meet the establishment requirements.

In Barrett, (1) an actual settlement was made with the plaintiff(s) who had filed suit; (2) the taxpayer denied liability when entering into the settlement; and (3) there was no indication that either settlement was not made at arm’s length. Under these circumstances, the Taxpayer has met the establishment test. This is going to be the typical scenario in a clawback situation.

Private Letter Ruling 200808019, though not authority, is an excellent statement of the law on this issue. It also establishes standards that were all met in the Taxpayer’s case.

– – –

Footnotes:

1/ The Mitigation does not seem applicable to a clawback of a principal payment invested in a Ponzi Scheme, since the principal payment does not represent the Taxpayer’s “income” from the Ponzi Scheme. This article focuses only on the clawback of “income items” reported by a Taxpayer that arises from a Ponzi Scheme.

2/ The two Pennzoil cases were ultimately decided on two principles, one of which was the “inventory exception”. There is an exception in Code Section 1341 that does not permit that section to apply to refunds of items related to “inventory income”. This is because the income tax treatment of “inventory items” have their own tax framework to allow for corrections. That overpriced oil sold by Pennzoil was inventory. All of the Appellate Court Judges agreed that the repayment by Pennzoil was a cost to Pennzoil that would be reflected in its inventory accounting.

Download this article as a .pdf

DO YOU HAVE ADDITIONAL QUESTIONS – CONTACT RICHARD S. LEHMAN TODAY! :

Error: Contact form not found.